Illusory Transformations: A Conversation with Han Duyi and Zhang Zhihui

Han Duyi creates objects and environments as “neuroaesthetic prescriptions.” He draws visual references from diverse cultural and temporal contexts, remixing them in unusual ways in order to evoke emotions and investigate the evolving structures of visual culture. Han holds a B. Arch from Cornell University. His work is in the collections of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and White Rabbit Collection (Sydney, Australia).

Zhang Zhihui is the founder of Mousa Art & Technology and a curator. Her curated exhibitions have been shown at institutions such as Goethe-Institut China, Beijing Inside-Out Art Museum, Amherst College, Three Shadows Photography Art Centre, the EU Delegation to China, and Hebei Museum. During her M.A. studies at Harvard University, she did research on Chinese contemporary art and history of science. Her writings have been featured in publications such as ARTFORUM China and LEAP and she has been invited to give lectures and talks at Long March Project, the KWM Art Center, and the British Embassy to China.

Cao: Could you briefly introduce the exhibition Resonance - Hebei Imaginations: Digital Cultural Heritage Exhibition that you recently curated?

Zhang: The exhibition is hosted by the Hebei Museum and produced by Mousa Art & Technology. It opened on July 7 and runs until October 10. As curator, I invited four artists and studios who are active in the field of digital technology and contemporary art. We worked with the digital data of the museum’s ancient artifacts, using its collections as our foundation and then layering on new creative work with the help of cutting-edge digital technologies. The theme, “resonance,” takes inspiration from the philosophy of “all things coexisting in harmony” that is embodied in Han dynasty (201 BCE – 220 CE) bronze design. We wanted to create a contemporary immersive exhibition that is both visually powerful and fun for audiences to interact with.

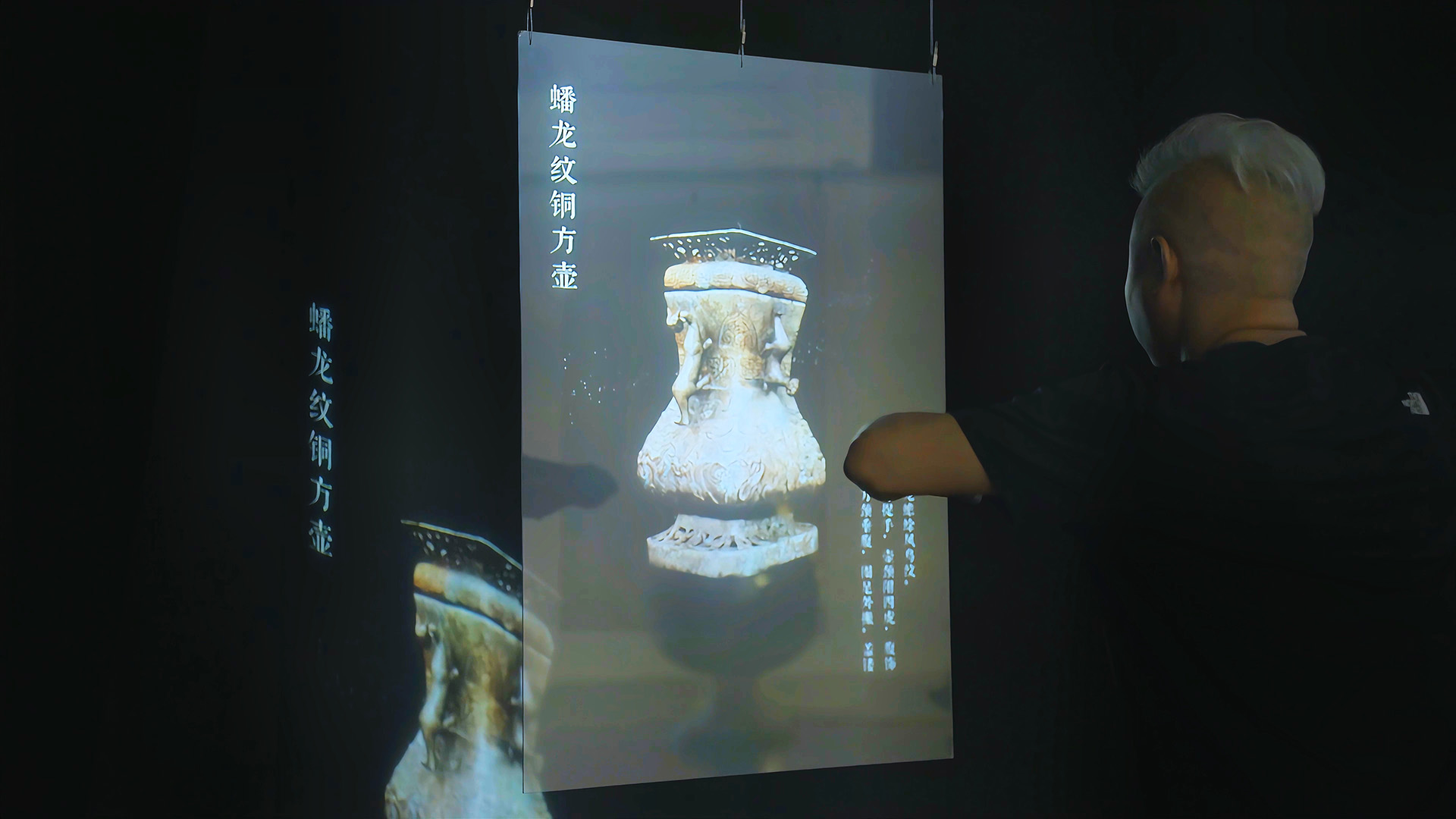

Zhang: Each artist chose an artifact from the museum’s collection that resonated most with them and then reimagined it through their own creative practices. For example, Han Duyi drew inspiration from the mountain-shaped incense burner (boshanlu) [see “Gilt-bronze Mountain-shaped Censer” below]. The ancients designed this everyday object with imagery of sacred mountains and fantastic beasts, turning it into a vision of cosmic harmony and a pursuit of spiritual ideals. Relight Studio focused on the bird-script inscriptions of a bronze ewer, bringing to life the elegance and beauty that led ancient people to invent the bird-script calligraphy style. Zhang Zhexi took the eighteen-sided dice used in drinking games and transformed it into a trigger for fantastical gameplay, combining the early cosmological idea of unity between heaven and humanity with the dynamics of drinking contests in a multi-screen video installation. And IDLE Lab invited visitors to participate physically: by making spontaneous movements, the audience could summon virtual artifact models that mirrored their own gestures. Ultimately, our goal was to build a new creative platform, one that connects knowledge with technology through collaboration. We hope that ancient culture can continue to nourish us, and that the aesthetic wisdom and intangible heritage of the past can enrich everyday life today. Most of all, we wanted every visitor to the museum to feel welcomed into this dialogue between past and present.

Cao: Could you tell us about your work, Landscapes: Illusions in Flux, in this exhibition?

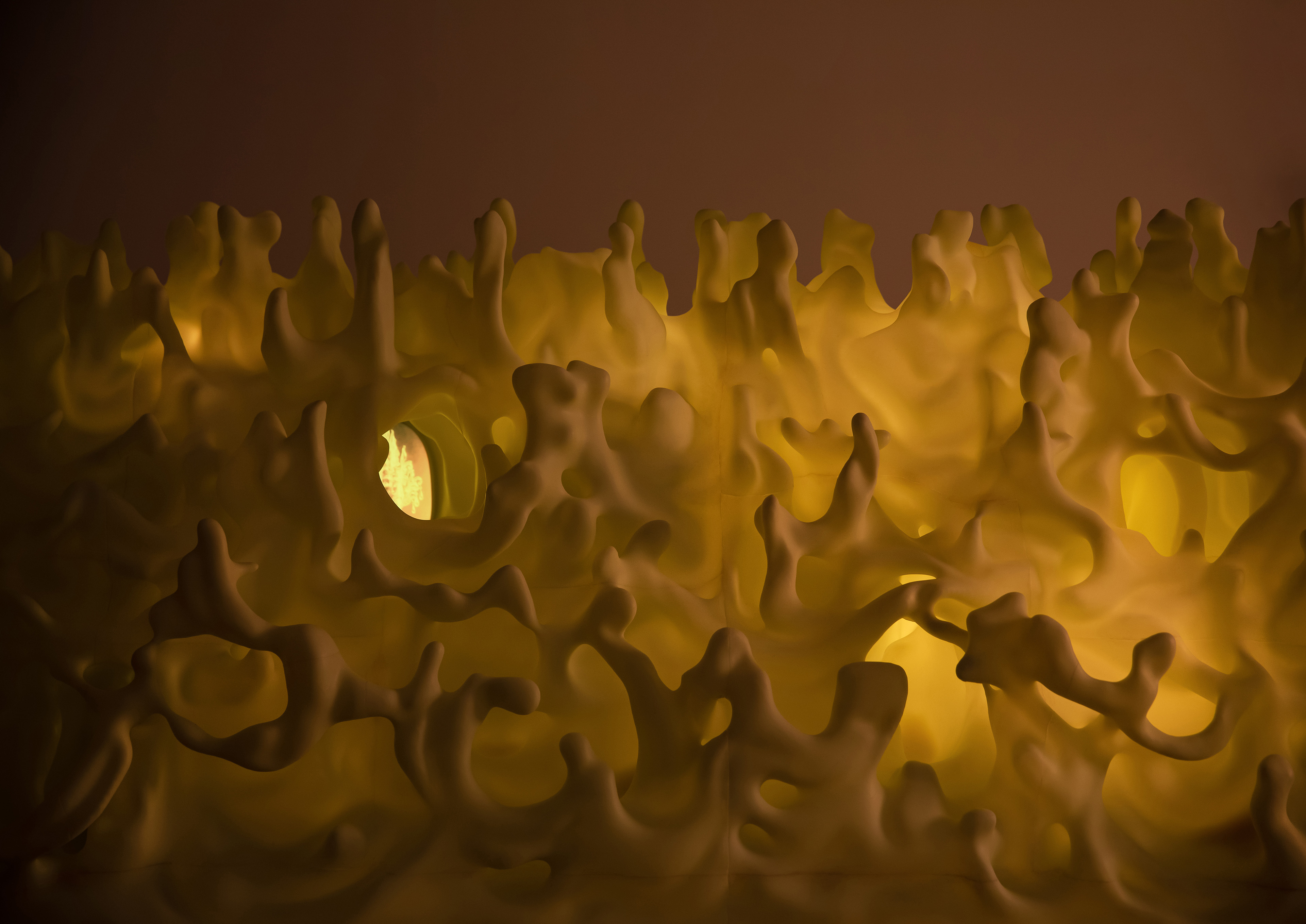

Han: This installation originates from a Western Han dynasty (206 BC - 202 CE) gilt-bronze censer. Using AI, I re-imagined the censor across different time periods, cultural contexts, and aesthetic systems. A palm-sized incense burner was 3D-printed into a life-size horizontal display cabinet. Its form evokes both clouds of mist and a handscroll landscape, while also resembling a strange living organism that keeps growing. Inside the structure are ten cave-like chambers, some intersecting with one another. Each chamber houses a LED screen, on which plays a looping animations of a thousand AI-generated variations of the censer’s typologies. The object’s identity dissolves through constant transformation, sometimes retaining recognizable features, sometimes morphing into entirely different objects, creatures, or even unidentifiable shapes. The visuals, presented in the style of old photographs, combined with light and music, evoke a sense of temporal collapse and semantic fluidity. I drew from the traditional idea of “mists and clouds” (yanyun) where the natural world measures time through constant transformation. It’s an interpretation of impermanence and psychological projection, reflecting on originality and uniqueness of art object in the AI era, and on the museum’s role in constructing meanings. What the audience encounters is not a fixed relic, but a mysterious computational organism: a porous container of unknown logic, holding and releasing images and emotions from the boundless universe that have yet to be named.

Cao: Could you expand on the role of AI generation and emotional response in this work?

Han: If you strip away the decorative motifs, the censer is essentially a container. Ornamentation projects an aesthetic system onto the object’s surface, giving it expressive power. Inside this small artifact lies an entire imagined world. When we look at an ancient object, we’re seeing one possibility of an “aesthetic system” realized at a specific point in time by its maker. But there are countless other “unrealized possibilities” running in the background. I wanted to use AI to imagine how might a cultural artifact manifest in different systems, across cultures, geographies, and times? We usually categorize artworks by nation, culture, or style, but you can also think of all these artifacts as different “solutions” appearing at different coordinates within the same system. Like an AI algorithm, or a DNA sequence, the aesthetic system itself contains infinite generative potential. The AI variants in my work respond to that relational, fluid, and ever-changing possibility. In the creation process, I also pay attention to moments that give me strong feelings, then I ask: can this feeling be shared? Can others resonate with it? For this installation, you’re first drawn to the massive censer, then notice shifting lights and shadows that makes you think of the idea of a landscape painting. Moving closer, peeking into the caves, you encounter ever-changing forms. There’s a sense of discovery, almost like treasure hunting.

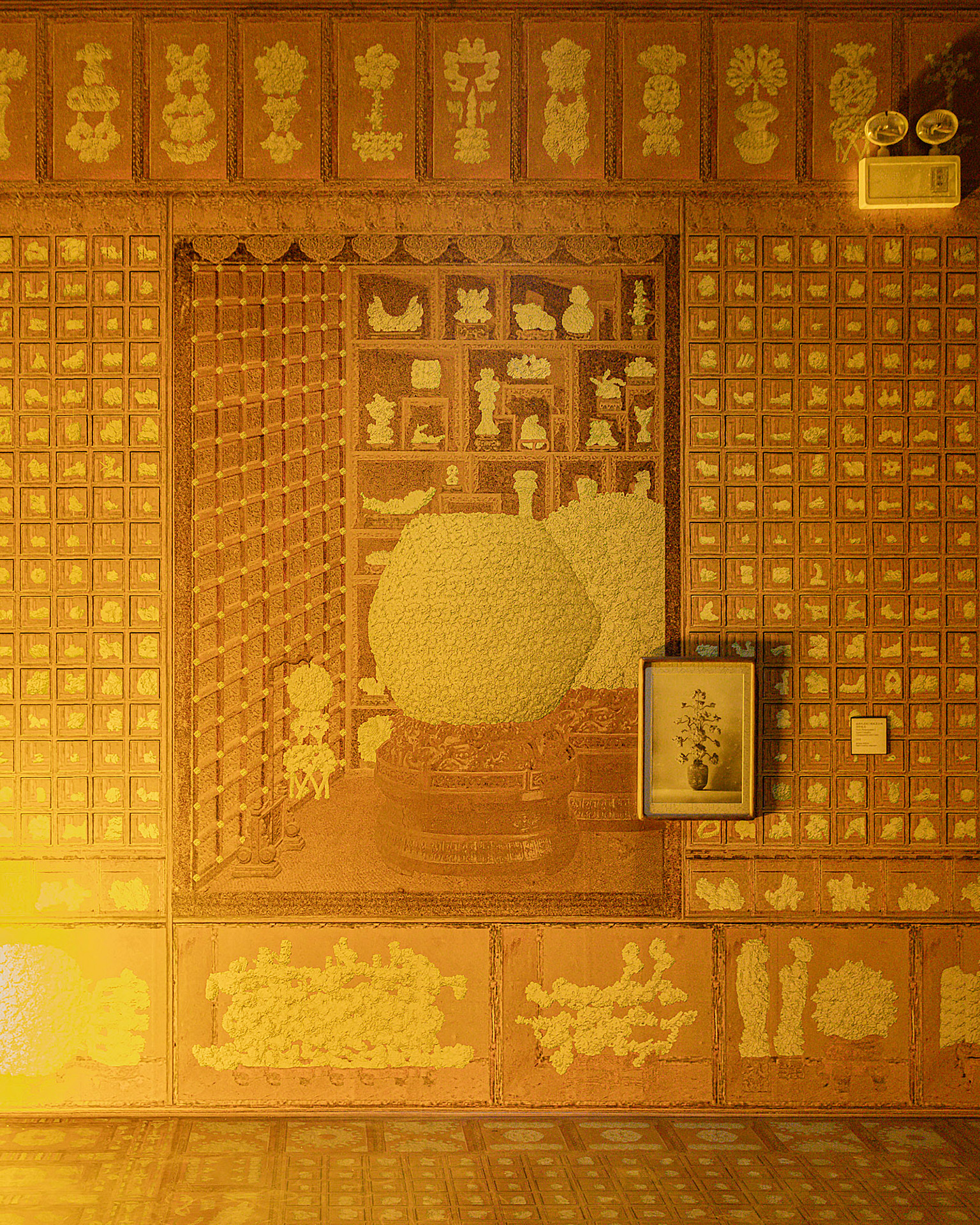

Cao: In your earlier work Visions of Bloom, you also applied a generative system to create a multitude of cultural artifacts. Could you talk about that?

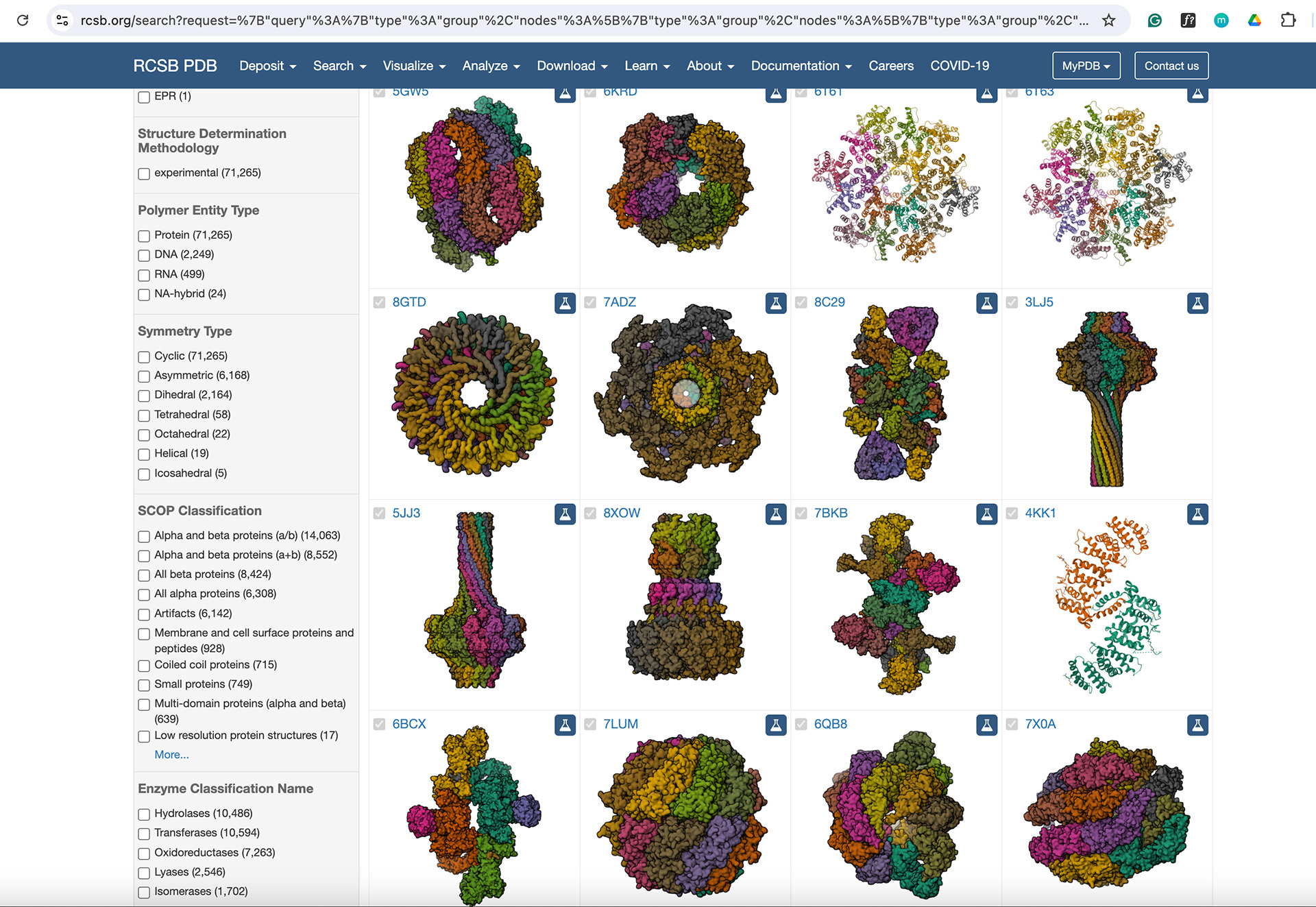

Han: The two works are connected. At first, I was fascinated by curio cabinets (duobaoge) and ceiling grids in Qing dynasty (1644-1912) palaces. They reminded me of protein databases: a glowing matrix linking things together. Like the Landscapes: Illusions in Flux, Visions of Bloom treats artifacts as evolving systems. In the Qing dynasty, the aesthetic system reached an extreme level of ornate yet complete: architecture, interior designs, and paintings, they were driven by a desire to compile earlier traditions. The antiquarian motif (bogu wenyang) epitomizes this impulse to collect and contain everything. Curio cabinets, with each small compartment, visually embody that mindset. When I stumbled upon a protein database online and browsed the 3D models, I felt something similar. The molecular structures resembled miniature landscapes and scholar’s rocks. Conceptually, proteins are a natural “generative system” with a clear evolutionary logic: amino acids combine in sequence, molecules grow more complex, and a single shift in shape creates a different compound. This tendency toward complexity is also felt in Qing dynasty visual culture. So, I juxtaposed the “man-made system” with the “natural system” to create Visions of Bloom.

Cao: How do you see the role of digital technology in museums?

Zhang: Digitization is already widely used for conservation. Both movable and immovable artifacts are 3D scanned, not only to reveal details invisible to the naked eye, but also to support reconstruction and restoration. In the context of display, digital tools can “activate” artifacts by drawing viewer’s attention to craftsmanship and detail. But digital technology also has its own medium specificity. It isn’t just about reproduction; it carries its own expressive traits. For our project at the Hebei Museum, we thought a lot about this. Our artists first browsed the museum’s digitized 3D models online, selecting familiar or distinctive artifacts that could spark resonance. Then, through research and comparison, they dug deeper into the objects’ meanings. Finally, using appropriate digital media, they created new presentations that offered audiences fresh experiences. Honestly, this kind of activation isn’t easy and it’s still at an early stage. To go deeper, we have to rethink curatorial narratives and viewer experiences. Technology should serve the questions we’re asking and the ways audiences can relate to and understand, not just to show off.

Han: From my perspective, the benefit of digitization is that you don’t need to be physically present to grasp both the “whole picture” and “minute details.” Things that no longer exist can be revived through rendered videos or virtual reality. For example, we can better understand what a Roman palace looked like back then. For fragile artifacts, high-resolution 3D scans allow them to exist in another form. As more artifacts are digitized, humanity’s cultural system becomes more accessible and interconnected. And digital technology itself will gradually “grow” new elements within that system.

Cao: How do you see contemporary art entering traditional museum spaces?

Zhang: This exhibition was an attempt at bridging between contemporary art and cultural heritage. The contemporary pieces must stand on their own while also pointing back to the ancient artifacts. We move back and forth between these two poles. Such interventions are never seamless, and there will be collisions and questions. Some contemporary works demand more from the audience, which doesn’t always match traditional museum goers’ expectations. As a curator, I need to consider audience expectations and how they want to engage. If we suddenly present complex and dense works that require deep reflection, many visitors won’t be ready. So, for this exhibition, we broadened the spectrum: some works allow quick immersion, others call for sustained thought.

Han: For my piece, the focus is still on “digitization of artifacts,”—that is to use technology to deepen audiences’ aesthetic experiences and historical understanding. Strictly speaking, this isn’t yet about “contemporizing” the artifact. The real question is: how do we connect it with today’s value systems? In my other projects, I’ve experimented with more organic connections and that’s where I want to keep exploring. Cultural heritage museums now often include contemporary art, and contemporary art often incorporates elements of ancient artifacts. For creators, the core issue is: how do we connect ancient artifacts with contemporary values, emotions, and zeitgeist? I believe that if you temporarily set aside the materiality, the design logic and aesthetic “base tone” of ancient artifacts can actually align with the present. Unearthing their fluidity and linking them to our own time is a crucial step.

Cao Mengge researches painting’s formats and viewer experiences in medieval China. He also develops curatorial narratives for the Dispersed Chinese Art Digitization Project (DCADP), a collaborative initiative that reconnects displaced art objects with their source communities and broader audiences. Cao holds a PhD in art history from Princeton University, and he is a postdoctoral scholar at the University of Chicago.