Viewers of the Imperial Procession Reliefs

The Imperial Procession Reliefs (c.500–523 AD), now housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, continue to captivate visitors from around the world (Fig 1a and 1b). Long before they were removed from the Binyang Central Cave at the Longmen Grottoes, these magnificent stone carvings had already drawn attention. Artists and scholars reproduced them through paintings, rubbings, and early photography, leaving behind a rich visual record. Today, these materials help us trace how people have viewed and perceived the reliefs over time.

Although the construction of the Longmen Grottoes began in the Northern Wei dynasty (386–534), they did not appear in visual representation until much later. In 1797, Huang Yi (1744–1802), a prominent epigraphist and artist in the Qing dynasty, visited the site to study its stone inscriptions and carved steles. Inspired by what he saw, Huang created a painting album that included some of the earliest known depictions of the grottoes. In one of the album’s leaves, titled Longmen Mountains, Huang illustrated the hillsides dotted with niches and caves, viewed from across the Yi River (Fig 2a). On the right side of the composition, three large caves—known as the Binyang Caves, where the Imperial Procession reliefs once stood—are clearly visible. On the left, the monumental form of Fengxian Monastery rises, anchoring the landscape with a commanding presence. Remarkably, Huang’s rendering of the caves and the mountain silhouette closely resembles what we still see at the actual site today (Fig 2b).

Huang’s depiction of the Longmen Grottoes reveals his primary interest in carved inscriptions rather than Buddhist sculptures. In the painting leaf titled Yi River Pass (Yi Que), he portrays a vivid scene inside a cave, where he and his assistants are shown making rubbings from the carved niches (Fig 3). On the right, a person on a ladder is using a tool to flatten the damped paper onto the lower part of a niche, where the dedicative inscription is located; on the left, another figure gestures toward the base of a niche while conversing with a man in a white robe and shaven head, likely a monk. Huang’s own inscription beside the painting conveys both his excitement at discovering an early Tang dynasty text with the help of a monk and his regret at being unable to take rubbings of inscriptions that were too difficult to reach. However, both the painting and its accompanying text pay little attention to the Buddhist icons within the niches, which are rendered in a loose, sketchy manner, devoid of precise detail.

It is highly likely that Huang Yi saw the Imperial Procession reliefs in the Binyang Central Cave, but could he have had rubbings made of them? Rubbings of pictorial relief carvings were a relatively late development. Monk Liuzhou (1791–1858), renowned for his mastery of the "composite rubbing" technique, created a painting that integrated rubbings from a miniature Buddhist stone shrine he had acquired in 1836 (Fig 4). This method allowed him to represent not only the carved relief surfaces but also different facades of the object, producing a quasi-three-dimensional effect. More examples of pictorial rubbings featuring Buddhist sculptures and reliefs began to appear in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. However, these were typically small in scale, often supplementing inscribed niches and formatted as scrolls. The monumental scale of the Imperial Procession would have posed a considerable challenge for rubbing makers, who were more accustomed to capturing inscriptions on bronze vessels or small stone carvings.

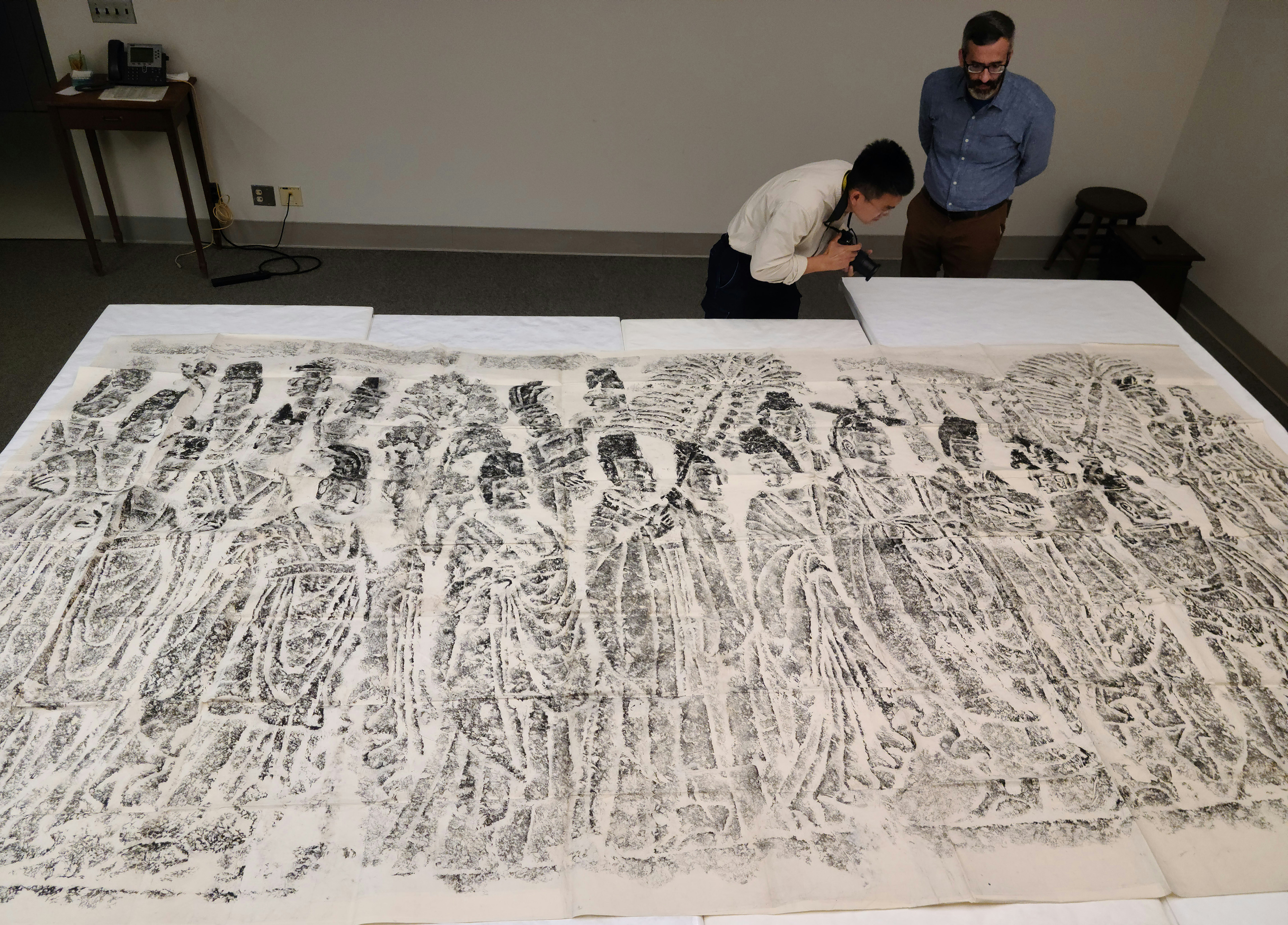

Surprisingly, around 20 sets of rubbings of the Imperial Procession relief survive today in museums around the world. Most of them were made not long before the reliefs were removed from the Binyang Central Cave in 1930s. The materials and techniques used for these rubbings differ significantly from traditional methods. Because of the relief's monumental size, the rubbing makers had to use multiple pieces of paper cut into various shapes and joined together to cover the entire surface (Fig 5a). To capture the three-dimensionality of the reliefs, the artisans used a technique of repeated ink dabbing. This process created a subtle layering effect, helping to distinguish raised and recessed areas of the carving. When comparing different sets of rubbings, small but telling variations begin to emerge. In the version held at the Cernuschi Museum in Paris, for instance, one figure appears in a full frontal view, while in other versions, the same figure is shown in profile (Fig 5b). These discrepancies suggest that when the artisans assembled the separately made paper segments, their interpretations of the relief’s form varied.

These rubbings offer fascinating insights into how different artisans perceive the Imperial Procession Reliefs. When gently pounding ink-soaked pads onto paper pressed against the carved surfaces, the makers effectively "saw" through their hands. Variations in pressure and angle during this process produce unique visual outcomes, ensuring that each rubbing remains distinct (Fig 6a). Furthermore, since the process of rubbing-making collapses the distance between the carved stone surface and paper, it provides an extreme close-view that isolates the reliefs from their spatial environment. This flattening of the three-dimensional carving creates the illusion of a continuous image, masking the fact that part of the relief originally curved around a corner within the cave. For example, in the rubbing of the Emperor Procession Relief, the left one-third portion corresponds to the north wall of the Binyang Central Cave, while the remaining two-thirds come from the east wall (Fig 6b).

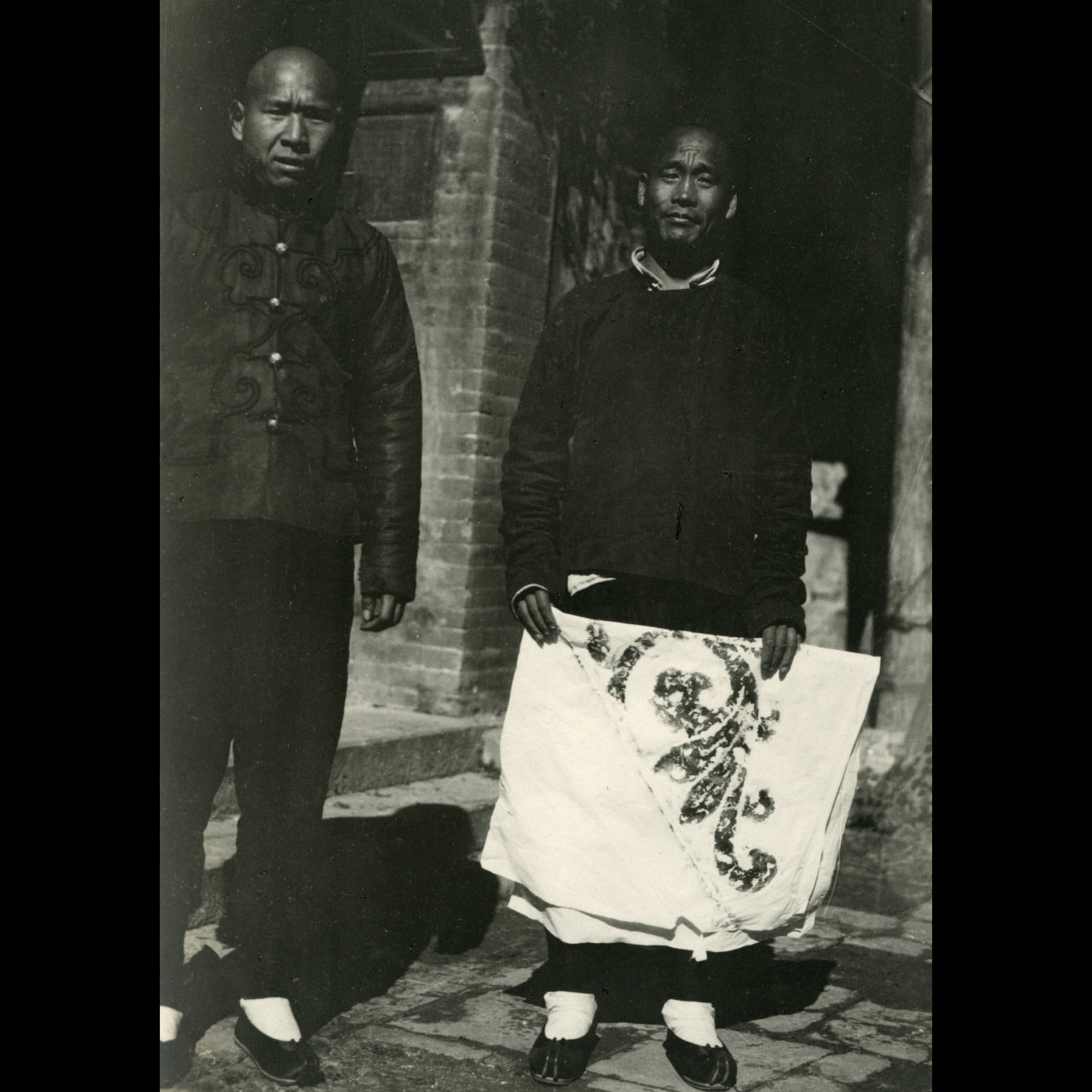

Unfortunately, we have few biographical records about the makers of these rubbings. In 1910, when the American collector Charles Freer (1854–1919) visited Longmen, he hired several artisans to produce rubbings of the inscriptions and reliefs in the caves (Fig 7a). Freer's diary refers to an individual surnamed "Tsung," possibly Zong Huaipu, a renowned rubbing maker who maintained close ties with scholars and archaeologists in Henan province. Additionally, one of early photographs of the Guyang Cave shows a graffiti by a rubbing maker named Gao Mingshan and is dated to 1910, overlapping with Freer’s presence in Longmen (Fig 7b). Regardless of their identities, these artisans rose to the challenge of transferring the intricate details of the Imperial Procession Reliefs onto paper, capturing nuances that photography at the time could not easily reproduce.

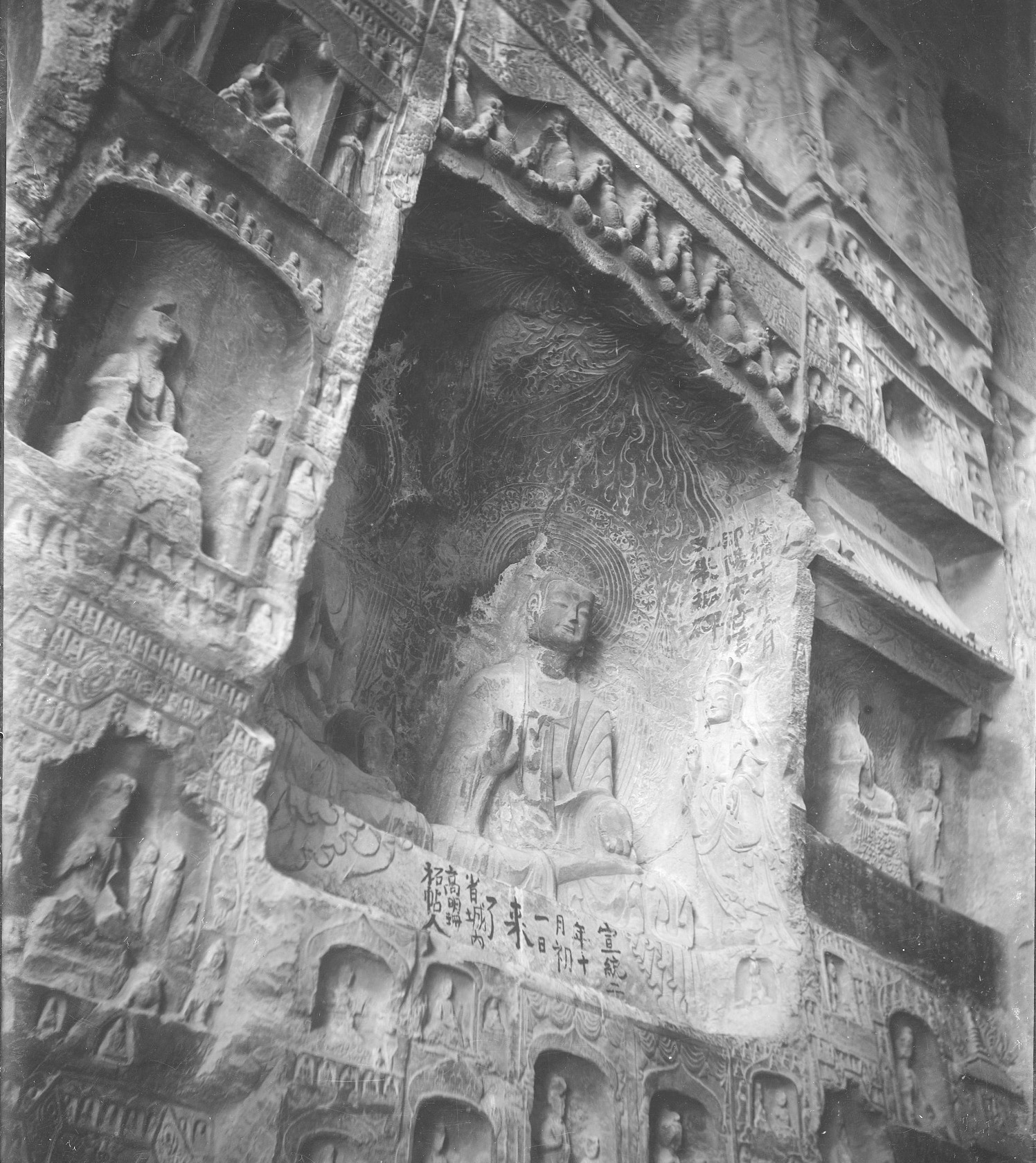

Compared to the surviving rubbings, most of which were created by anonymous artisans, the early photography of the Imperial Procession Reliefs has a more traceable lineage. In 1904, Japanese photographer Hayasaki Kōji (1874–1956) visited the Longmen Grottoes and produced the earliest known photographs of the reliefs, along with images of the statues in the Binyang Central Cave. In one of these photos, Hayasaki captures Empress Wenzhao and two court ladies in a composition reminiscent of the Great Eleusinian Relief (Fig 8a and 8b). This visual parallel, either intentional or shaped by the camera’s aspect ratio, reflect a common tendency among early 20th-century viewers to draw connections between the Imperial Procession Relief and the aesthetics of Classical and Renaissance traditions. The photograph was later reproduced as a postcard by Yamanaka & Co., a prominent art dealer known for marketing Japanese and Chinese antiques to collectors in Europe and the United States.

In 1907, French sinologist Édouard Émmannuel Chavannes (1865–1918) visited the Longmen Grottoes and hired Chinese photographer Zhou Yutai from a studio in Beiping (present day Beijing). When photographing the Imperial Procession Reliefs, Zhou paid close attention to their spatial context by including adjacent bodhisattva statues and the sections where the relief curves around the corners of the northern and southern walls (Fig 9a). In doing so, Zhou treated the reliefs not as flat, isolated images but as sculptural works integrated into three-dimensional space. He returned to photograph the Binyang Central Cave again in 1910, this time commissioned by American collector Charles Freer. On this occasion, Zhou positioned his camera farther back to capture the entire relief within a single frame (Fig 9b).

Hayasaki and Zhou’s photographs were created through a complex technological process involving controlled exposure of glass plates coated with a gelatin emulsion of silver bromide. To bring sufficient light into the dim interiors of the cave, the photographers likely used mirrors positioned to reflect natural daylight, resulting in occasional bright, overexposed areas within their images. Unlike modern instant photography, these glass plates had to be carefully stored after exposure and later transported to a darkroom for development. This significant delay between taking the photograph and seeing the final image created a "belated vision," reminiscent of what Roland Barthes describes as photography’s unique power to capture a moment that "has been,” an experience simultaneously marked by presence and loss. Thus, these early photographs are not merely a representation but an “ indexical trace,” connecting us intimately yet hauntingly to a moment already past.

Photographs by Hayasaki and Zhou helped recast the Binyang Central Cave reliefs as modern “art objects.” As art history took shape in the early twentieth century, photography became central to both teaching and research. Swiss art historian Heinrich Wölfflin (1864–1945), founder of the formalist school, argued that photography not only transforms three-dimensional sculpture into flat images, but also dictates specific viewing angles—thus shaping how artistic style is interpreted. As the photographic images of the Imperial Procession Reliefs as well as other Buddhist sculptures found in China circulated worldwide, museums and private collectors began to seek out these religious artefacts for their aesthetic value (Fig 10). Yet this desire also fueled the large-scale destruction of Buddhist caves and temples, as well as the wide dispersal of Chinese cultural heritage during the early twentieth century.

Paintings, rubbings, and early photographs let us glimpse how past viewers saw and perceive the Imperial Procession Reliefs. Some chose to emphasize their connection to inscriptive practices, others drew attention to their material surfaces, and still others situated them within a spatial environment. Each time the reliefs are captured, new meanings and interpretations can emerge, and over time the ways of seeing them shifted in response to changing imaging technologies. Today, with tools like 3D scanning and modeling, digital reconstruction, and extended reality (XR), we can layer contemporary perspectives onto those earlier encounters (Fig 11). By manipulating camera angles, adjusting simulated light effects, and moving within the space with our bodies, 3D imaging afford an embodied and kinesthetic mode of viewing. What fresh interpretations might emerge, and how do they echo or complicate historical experiences? Let us look at reliefs again, with fresh eyes.

Cite this Article as:

Mengge Cao, “Viewers of the Imperial Procession Reliefs,” in “Longmen Binyang Central Cave Digitial Restoration,” Dispersed Chinese Art Digitization Project, 23/12/2025, https://caea.lib.uchicago.edu/dcadp/en/longmenbcc/viewers/.

Further Readings

- Abe, Stanley. "The Modern Moment of Chinese Sculpture." Misul Charyo 82 (2012): 63–92.

- Coleman, Fletcher. "Fragments and Traces: Reconstituting Offering Procession of the Empress as Donor with Her Court." Orientations 49, no. 4 (2018): 94–101.

- Hatch, Michael. Networks of Touch: A Tactile History of Chinese Art, 1790-1840. Perspectives on Sensory History. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2024.

- McNair, Amy. Donors of Longmen: Faith, Politics and Patronage in Medieval Chinese Buddhist Sculpture. University of Hawai'i press, 2007.

- Wang, Cheng-hua. "New Printing Technology and Heritage Preservation: Collotype Reproduction of Antiquities in Modern China, Circa 1908-1917." In The Role of Japan in Modern Chinese Art, edited by Joshua A. Fogel. 2012.

- Wu Hung. "On Rubbings: Their Materiality and Historicity." In Writing and Materiality in China: Essays in Honor of Patrick Hanan, edited by Judith T. Zeitlin, Lydia H. Liu, and Ellen Widmer. Harvard University Asia Center, 2003.

- Wölfflin, Heinrich, and Geraldine A. Johnson. "How One Should Photograph Sculpture." Art History 36, no. 1 (February 2013): 52–71.

- 查尔斯·兰·佛利尔,李雯(译),王伊悠(译),霍大为(译),《佛光无尽: 弗利尔1910年龙门纪行》,上海书画出版社,2014。

- 王正华,《走向公开:近现代中国的文物论述、保存与展示》,浙江大学出版社,2025。

- 巫鸿,施杰(译), "说'拓片':一种图像再现方式的物质性和历史性(2003)",《时空中的美术:巫鸿中国美术史文编二集》,生活·读书·新知三联书店,2009:83–108。

- 日向康三郎,吕静(译), 叶睿隽(译),《北京山本照相馆:日本摄影师和他镜头下的近代中国》,上海书画出版社,2021。

- 萧依霞,《峥嵘巨幅:克利夫兰艺术博物馆藏帝后礼佛图巨型拓片修复实录》, 典藏古美术 345. 6(2021): 44–51.

- 薛龙春,《古欢:黄易与乾嘉金石时尚》,生活·读书·新知三联书店,2019 。

- 赵淑梅,周立,杨超杰, 《龙门旧影》, 上海: 上海交通大学出版社,2021。

- 张萌,《帝后礼佛图拓片考》,收藏家 2 (2022):97–104。

- 関紀子,《東京国立博物館が所蔵する早崎梗吉の写真資料について 一茨城県天心記念五浦美術館が所蔵する早崎梗吉日記との照合から一》, アート‧ドキュメンテーション研究 20 (2013):18–36。