A Ming Buddhist Temple and Its Architecture

Completed in 1444, the ninth year of the Zhengtong reign, the Zhihua Temple was among a handful of Buddhist temples whose constructions were granted by the imperial edict issued directly from Emperor Yingzong. Under the auspice of this very emperor, the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) witnessed the nation-wide construction of Buddhist temples in large quantity. Unfortunately, most of them have either disappeared or been altered in modern times, and today, it is rare to find Ming Buddhist temples still retaining much of their original architecture. The Zhihua Temple, the most complete Ming Buddhist temple to have survived today, preserves a slice of the temple’s history, and offers a glance into some essential features that characterize Ming Buddhist architecture.

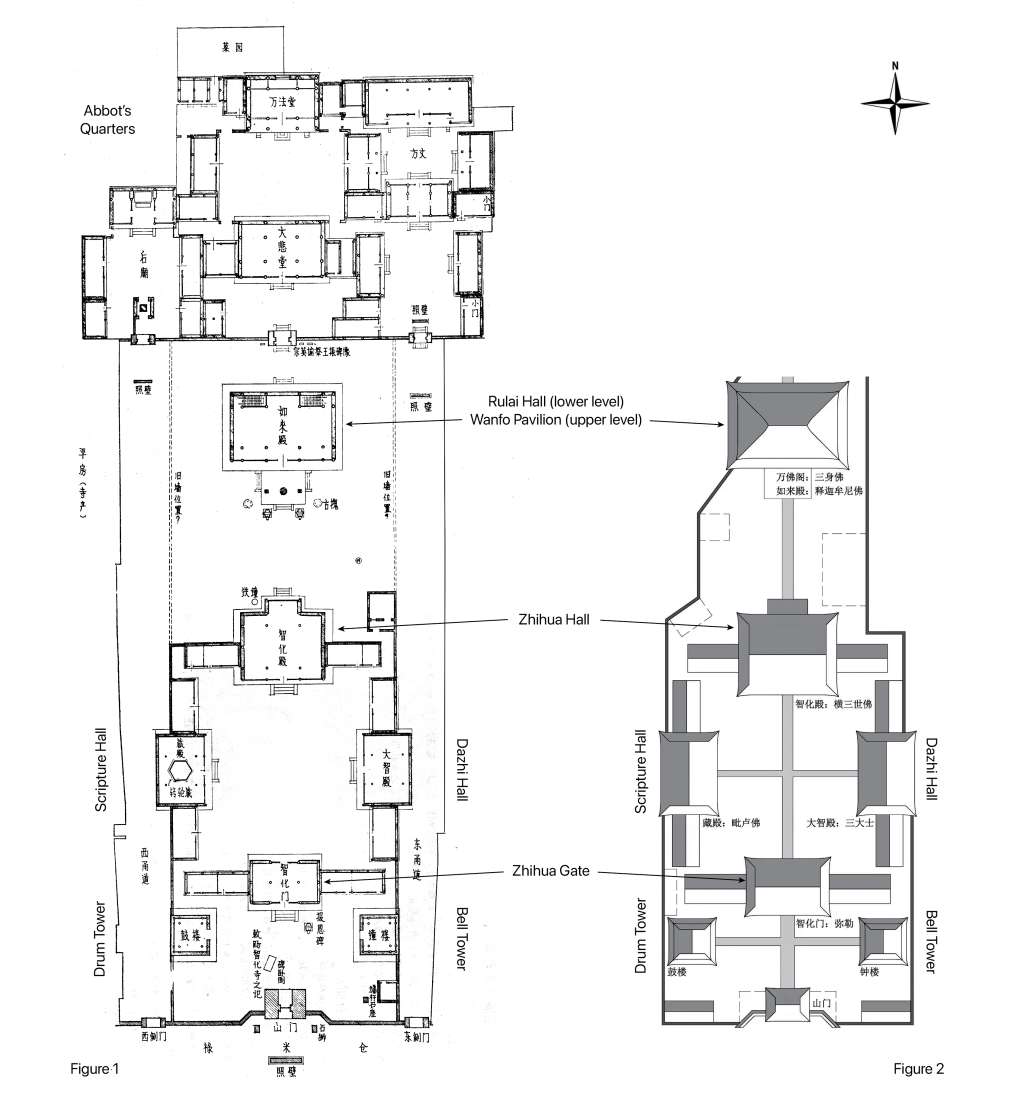

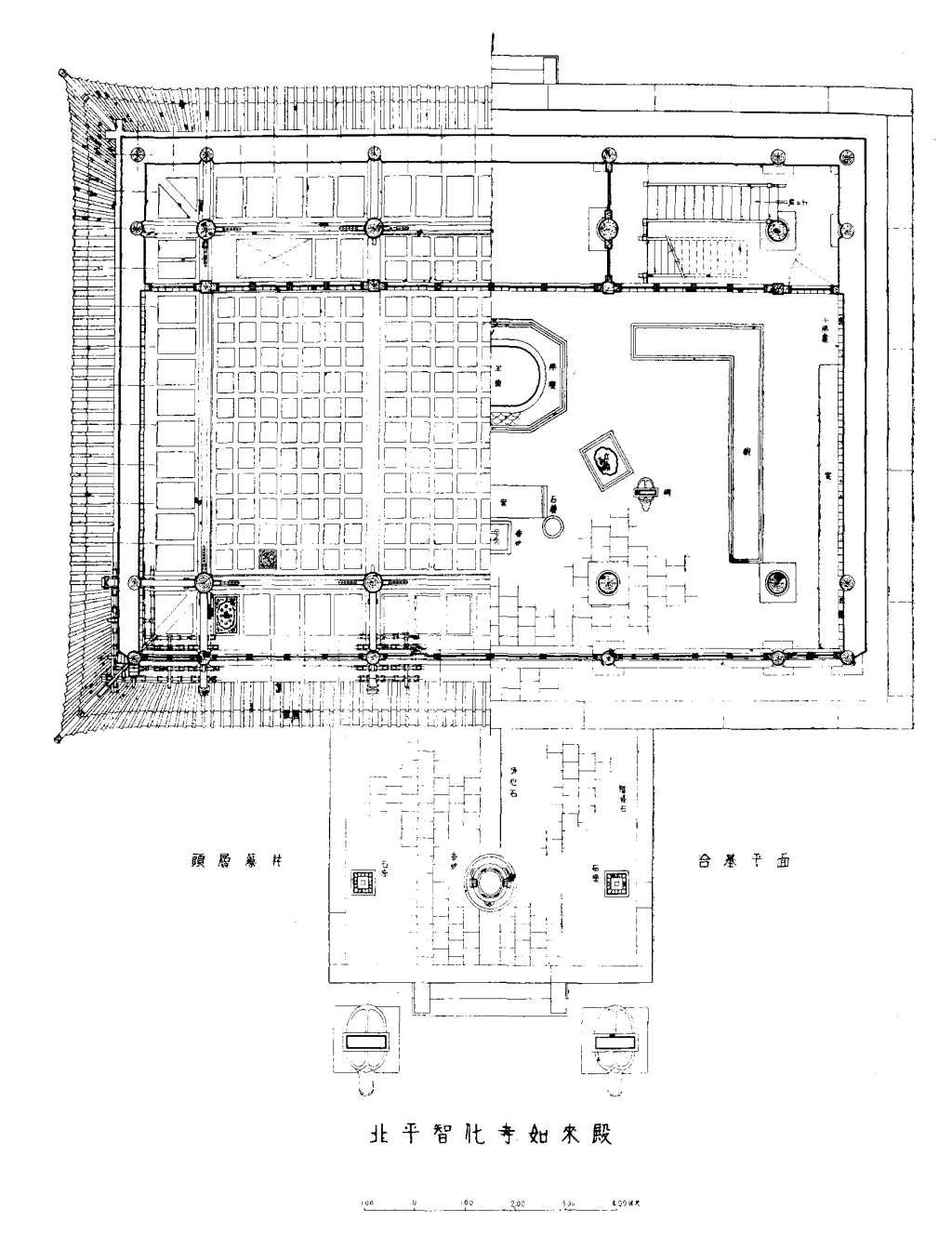

The temple layout is dominated by a central north-south axis, along which the principal halls are located. Each hall is fronted with a courtyard and two subsidiary buildings facing each other to form a "quadrangular enclosure". The only exception is the third building, the two-level structure—the Rulai Hall (Hall of Śākyamuni) on the first floor and the Wanfo Pavilion (Ten Thousand Buddhas Pavilion) on the second—enclosed by walls on its east and west. According to the first modern architectural survey of the temple during the early 1930s, it consisted of five quadrangular enclosures along the central axis (Fig. 1), with abbot's room and dormitories built along the two secondary axes that flank the central one in the rear section. Today, Zhihua Temple retains four original central quadrangular units (Fig. 2).

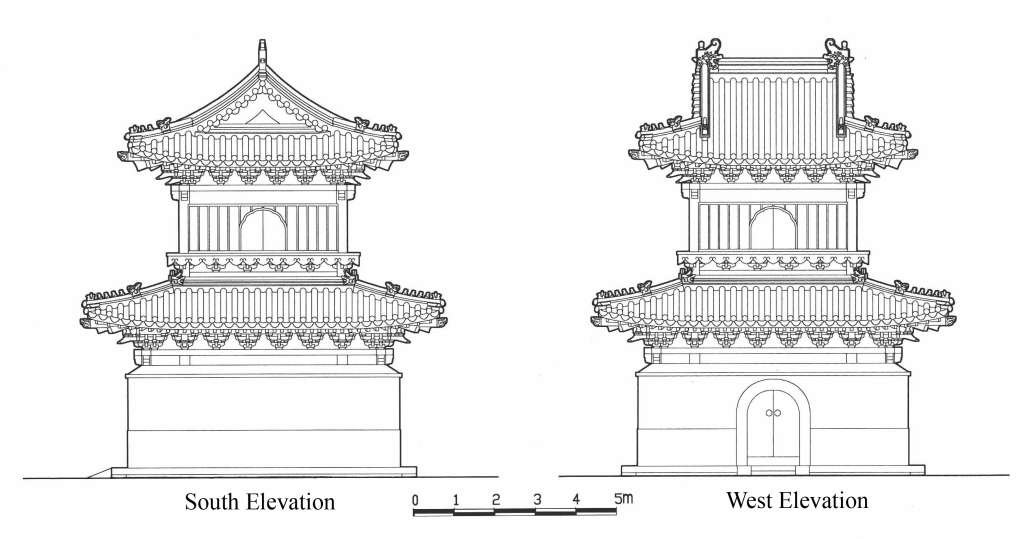

The rectangular plan, measuring 144 meters in length and 46 meters in width, has been typical for Buddhist temples since the Song period (960-1279). It is also customary to see a pair of tall structures—the Drum Tower on the west and Bell Tower on the east (Fig. 3)—immediately inside the entrance gate (shanmen). The entrance hall sitting on the north completes the first quadrangle. The entrance hall (Fig. 4), named Zhihua Gate, is a small structure with three bays across the front and two bays across the depth (13 x 7.8 meters). It originally contained four now-lost statues of the Four Heavenly Kings installed to guard and protect the temple. Taken together, the first quadrangle serves as a preparatory space before one makes entry into the main part of the complex to venerate the Buddhas.

The site’s center lies in the second quadrangle comprising the main Buddha Hall, the Zhihua Hall, and two subsidiary buildings, the Sutra Hall (Zang dian) on the west and Dazhi Hall (Hall of Great Wisdom) on the east. The Zhihua Hall (Fig. 5) is a 3-bay-by-3-bay structure (18 x 14.5 meters) with a hip-and-gable roof. It initially housed a Buddha triad with the Śākyamuni Buddha at the center along with eighteen Arhats. The only four interior columns form a spacious central bay before the altar for visitors to see and worship the Buddhas. Above this central area is where the grand coffered ceiling (approx. 5 x 5 meters), now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, was initially installed. The digitally reconstructed view (Figs. 6 and 7) shows how the coffered ceiling would have dominated the spatial center of the hall.

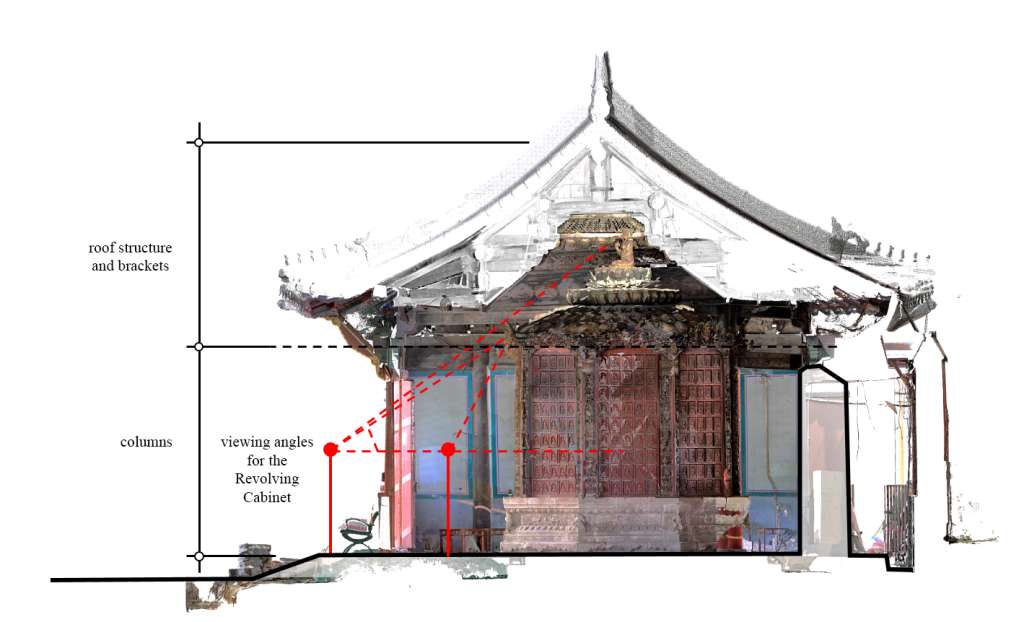

The Sutra Hall is a three-bay-by-three-bay structure (13.2 x 7.5 meters) with a hip-and-gable roof (Fig. 8). The primary function of the hall is to house an octagonal sutra cabinet, usually known as “Revolving Sutra Cabinet” (zhuanlun jingzang), although the one here has a stone plinth supporting the wooden cabinets and does not revolve. To accommodate the sutra cabinet, two front interior columns were removed to make fully visible the cabinet’s front side. Further, the sutra cabinet is not located at the center but slightly closer to the rear, leaving the space in the front for veneration. A Vairocana Buddha seated on a lotus is positioned right at the center on top of the sutra cabinet (Fig. 9). The off-center position of the sutra cabinet turns out to be a calculated decision, as it creates enough space and angle for a visitor to see the Vairocana Buddha right before s/he enters the hall (Fig. 10).

Opposite from the Sutra Hall is the Dazhi Hall (Fig. 11), east of the Zhihua Hall. The hall initially enshrined three bodhisattvas, Avolokiteśvara attended by Mañjuśrī and Samantabhadra on an altar. Though different in function and interior layout, the Dazhi Hall has the exact measurements and structure as the Sutra Hall, its counterpart across from the courtyard. This testifies to the remarkable degree to which the traditional timber-frame structure could accommodate diverse spatial arrangements without deviating from the norm that expects the two subsidiary structures to be similar in building form and structure.

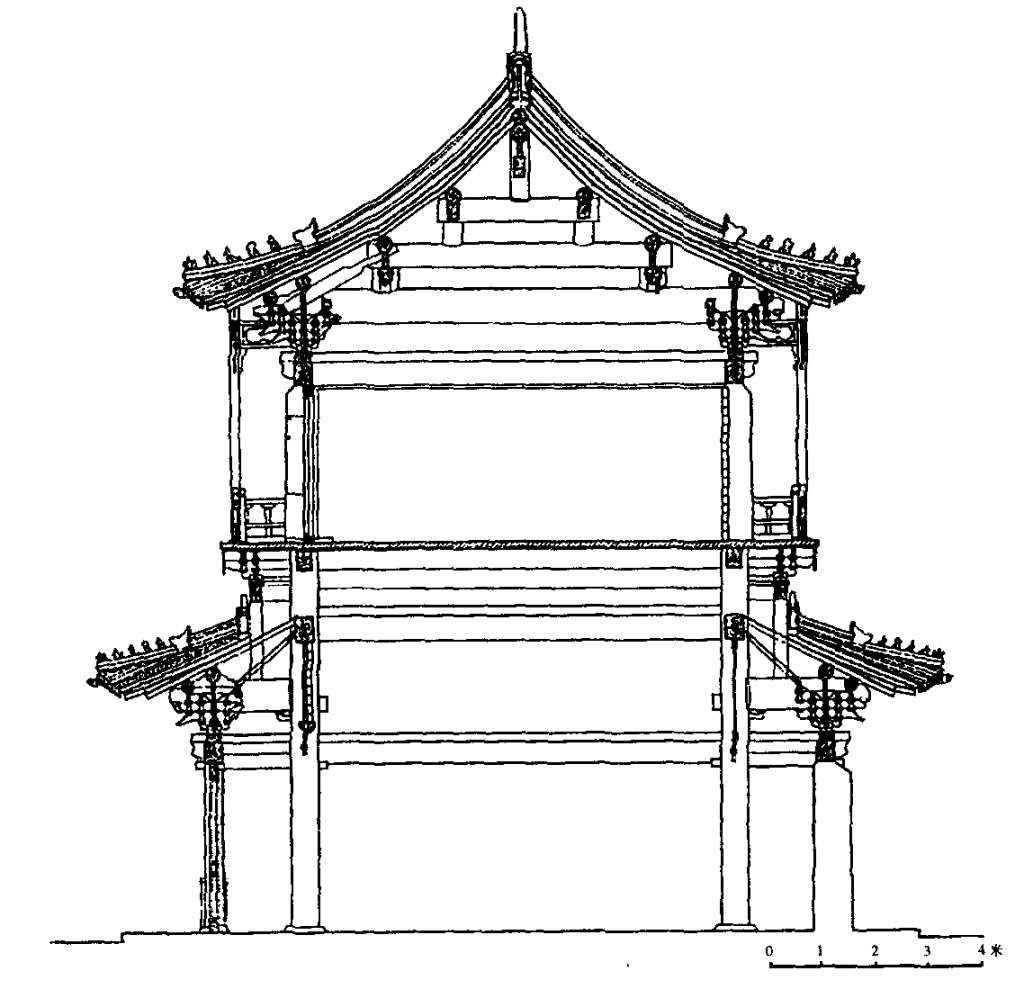

Rising behind the Zhihua Hall, the two-level pavilion in the third quadrangle is the climax in the architectural landscape of the temple precinct (Fig. 12). The lower level, called Rulai Dian (Śākyamuni Hall), has five bays across the front and three in depth, measuring 18 x 11.6 meters, and qualifies as the temple’s grandest structure. The upper level, the Wanfo Pavilion (Ten Thousand Buddhas Pavilion), is a smaller 3-bay-by-3-bay structure. Chinese multistoried pavilions could be multifunctional, with each floor serving different purposes from one another. Still, it is unusual to name each floor of the same multistoried building differently. However, despite using different names, the two levels of the multistoried structure were intended to be of a continuous vertical rise, structurally and iconographically.

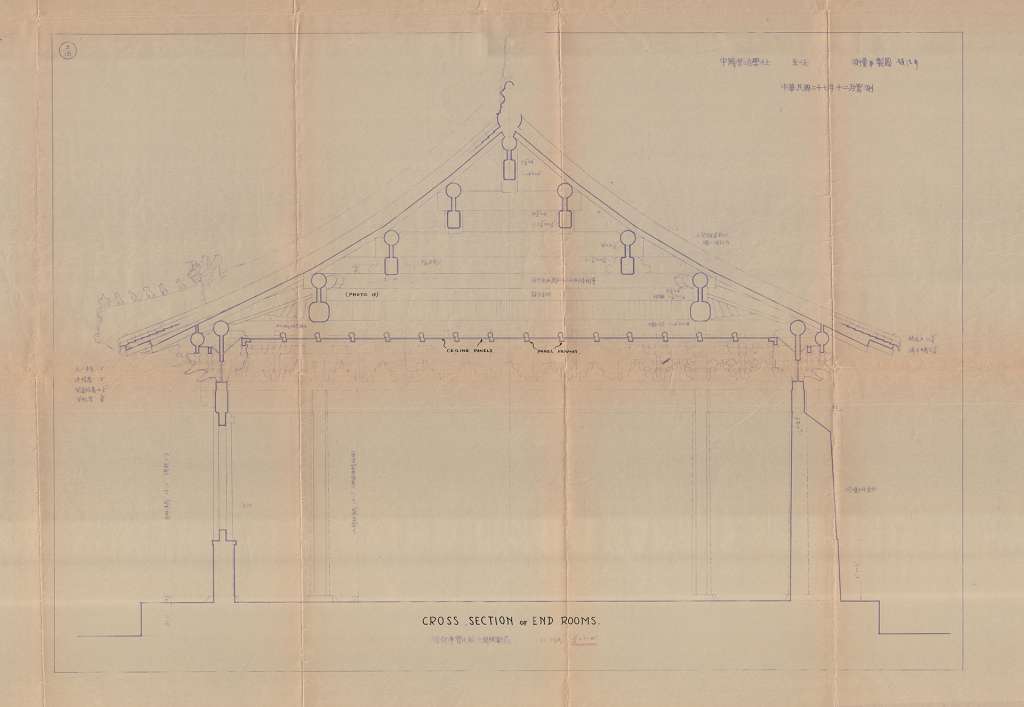

As the cross-section (Fig. 13) shows, the front and rear rows of interior columns on the first level stretch vertically up to directly support the upper level’s floor, on which the front and back brick walls stand. The style of vertical support thus opens the spacious room on both floors. The floor plan (Fig. 14) indicates a partition wall built on the lower level to further separate the interior into the front hall and a back area where the stairs are located. The front hall (Fig. 15) is thus defined by the partition wall and two side walls, all studded completely with small buddha images, each inside its niche. At the center is the iconic set of Śākyamuni and two celestial Kings, Indra and Brahma, flanked by two “L”-shaped sutra cabinets. The partition wall further continues upwards into the upper level, whose two side walls similarly are decorated with miniature buddha images (Fig. 16). The upper level features the “Three Bodies of the Buddha” (sanshen fo), with Buddha Vairocana at the center accompanied by Śākyamuni to its left and Rocana Buddha (Luzhena fao) to its right.

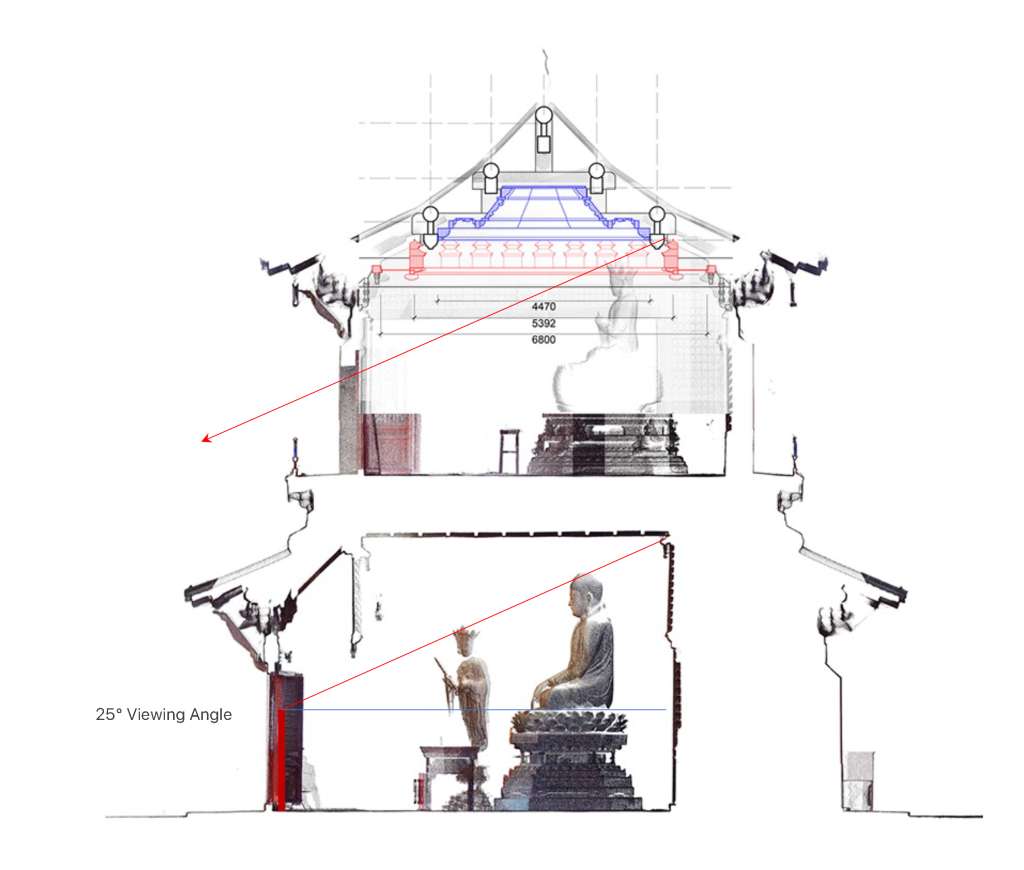

The two levels are, indeed, different. On the one hand, with the ceiling height at 5.87 meters, the lower level is more readily serving as a public veneration space. In contrast, the upper level has a much lower ceiling height at 5.13 meters because of the roof structure, suggesting a more intimate space perhaps for specific rituals or private visits. On the other hand, the ten thousand buddhas that cover both levels obscure physical separation and transform them into a much-unified vertical continuum. This verticality is also realized in architecture. While the lower-level ceiling is flat, consisting of square panels (tianhua), the ceiling on the second level features a magnificent coffered ceiling (zaojing), now installed in the Chinese gallery of the Nelson Atkins Museum of Art. In the digital reconstruction (Fig. 17), the coffered ceiling is at the apex of the entire elevation, seemingly oversize for the more intimate interior space on the second level, as seen in the point cloud of the cross-section produced by the scanner (Fig. 18).

The point cloud also shows the two main statues of the two levels are not aligned vertically. The statue of Vairocana is positioned further north, to leave enough space before it for visitors to pay homage to the Buddha with the coffered ceiling fully in view. Further, a visitor would gain a perspective of the entire interior on the first level at a 25° viewing angle. A visitor would also see the Vairocana Buddha on the second floor before reaching the building entrance with the same viewing angle (Fig. 19).

No doubt, Rulai Hall and Wanfo Pavilion together form the religious center of the temple. A glimpse of the Vairocana Buddha prompts and leads the pious visitor to enter. The Śākyamuni greets and shows the believer the Path with his Words, or dharma, collected in the sutras. The first level thus could be seen as a prelude to comprehending the cosmos of Buddhism that comprises numerous worlds, each presided by a Buddha, materialized in the ten thousand buddhas transforming the entire structure into a visionary cosmic space. The concept of that space is then embodied in the three bodies of the Buddha, with the Vairocana Buddha, under the coffered ceiling, as the center.