Temple History

The powerful palace eunuch, Wang Zhen, constructed the Zhihua Temple on his own property in 1444. Two tall stone stelae in front of the temple’s Zhihua Gate record the circumstances surrounding the temple’s construction. According to this record, Wang Zhen used his personal assets to build the temple in gratitude for the imperial favor that he enjoyed in the service of several Ming dynasty rulers. The temple was dedicated to the well-being of the nation and for the benefit of the people. In recognition, the reigning emperor Yingzong (r. 1436–49 and 1457–64) bestowed the name Bao’en Zhihuasi (Temple of Gratitude and Wisdom Attained) upon the temple. Despite its fine construction and lavish furnishings, the temple was completed in a brief period of time.

First introduced into the palace during the Yongle reign period (1403-1424) as a boy, Wang Zhen received a good education and was recognized for his intelligence. He became a favorite of Ming dynasty emperor Xuanzong (r. 1426-1435) and served as a tutor to his son, the crown prince. With emperor Xuanzong’s death, the young prince succeeded to the throne at the age of eight and as emperor, he continued to consider Wang Zhen as his teacher and advisor. He appointed Wang Zhen to head the most important eunuch agency, the Ceremonial Directorate (Silijian), that managed other eunuch offices. Among its duties was the inspection and review of state documents and memorials submitted for imperial attention. In theory, imperial China’s government recognized both financial and administrative distinctions between court and state. State administrators, from county magistrates to the chancellor, were subject to review and could be dismissed for incompetence or for corrupt activities. Eunuchs on the other hand, operated under the court budget, so they were not subject to those checks that restrained officers of the state administration. When the boy emperor appointed his revered tutor to such a powerful position, he in effect enabled Wang Zhen to abuse his position to interfere in state affairs and build a body of collaborators by rewarding those who flattered or bribed him, while punishing those who caused trouble.

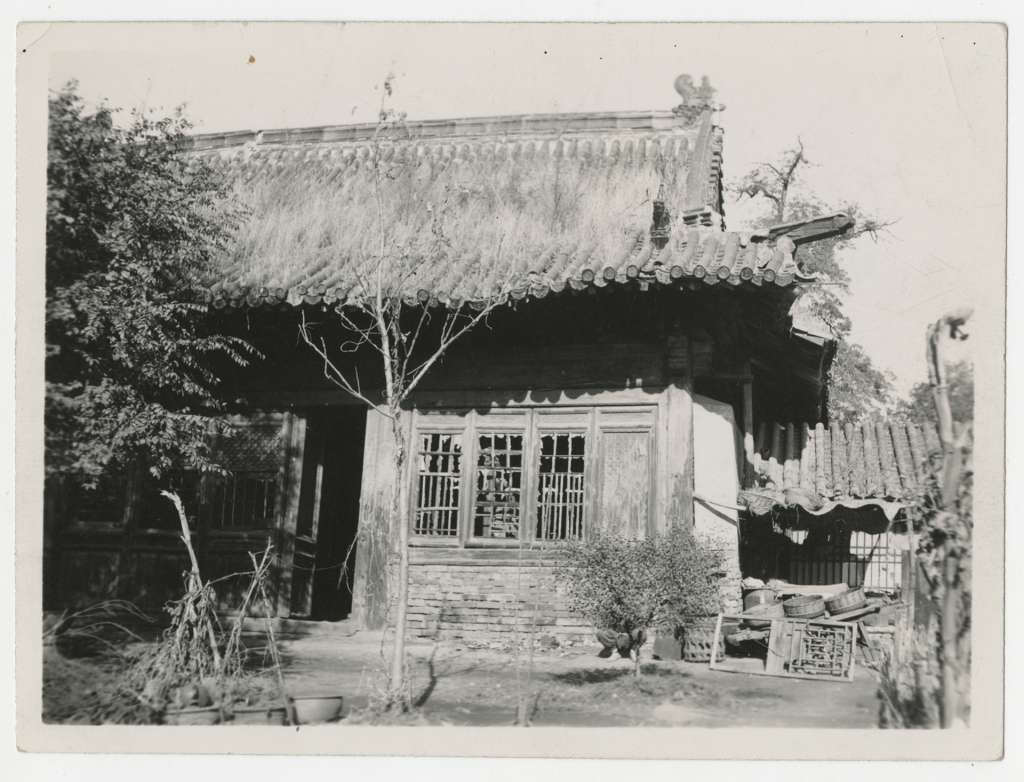

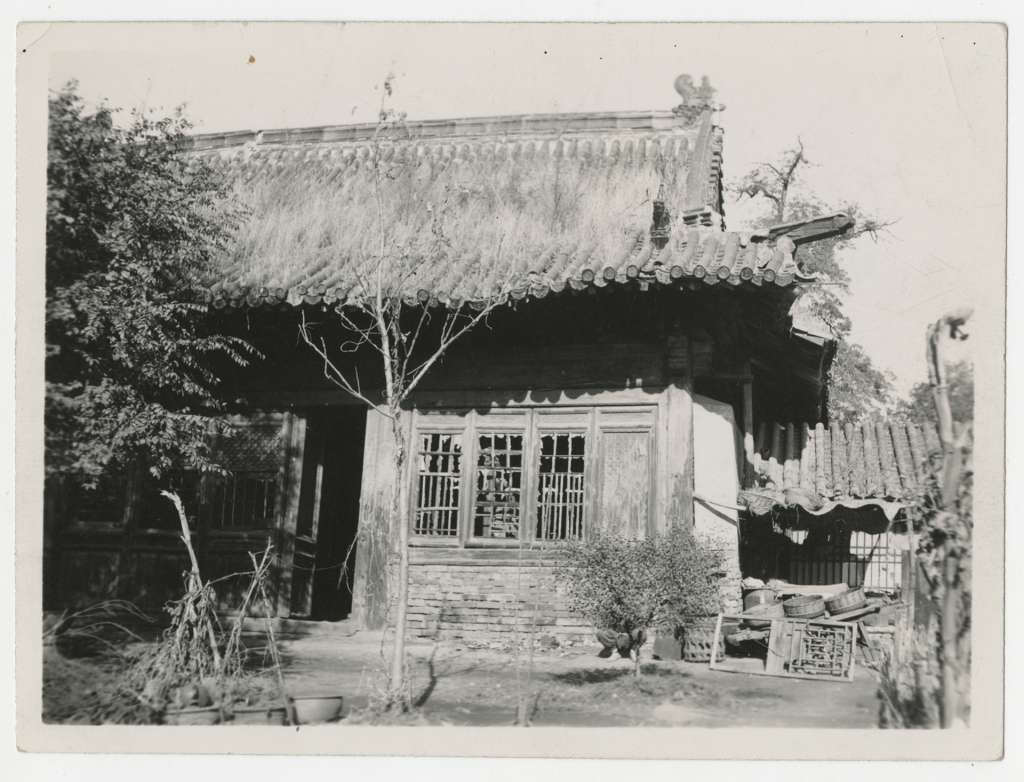

The Grand Empress Dowager Zhang, Yingzong’s grandmother, who acted as regent, objected to these abuses and, for a time, she was able to curb Wang’s corruption by means of an alliance with ministers at high levels of the state administration. However, when she died in 1442, Wang Zhen faced few obstacles and came to dominate national politics, including military campaigns. Wang implemented the construction of his personal residence and built the Zhihua Temple employing thousands of laborers, using expensive materials usually reserved for the imperial court. For example, the temple was furnished with special black-glazed roof tiles, elaborate ceiling panels, and large-scale Buddhist history with polychrome and gold ornament. Two main temple halls, the Zhihua Hall and Wanfo Hall, featured finely wrought wooden coffered ceilings with large central dragons set high above the principal Buddha images. A library of Buddhist scriptures was housed in a special Sutra Hall, where the texts were stored in a tall octagonal scripture cabinet set on a carved marble base. In 1449, against overwhelming civilian and military official advice, Wang Zhen persuaded the emperor to raise an army to go to war against the Mongols. Mongol tribal groups, who lived along the northern borders, had been sending horses and tributary envoys to the Ming government in exchange for rewards, but Wang Zhen cheated them of their payment and placed sanctions on border trade. Mongols resorted to raiding the northern borders. Yingzong and Wang Zhen both participated in battle, which proved disastrous when a Mongol cavalry (Ch. Yexian) ambushed the Ming army, killing Wang Zhen and many Chinese generals and capturing the emperor. Yingzong was held hostage for a year and was released and returned to Beijing after his brother was installed as emperor Daizong (r. 1450-1456). Yingzong eventually regained the throne in 1457 after his brother fell ill and died.

He revisited the Zhihua Temple to have a shrine built and a statue made in honor of his disgraced childhood tutor. He arranged for ceremonies to benefit Wang’s spirit commissioned a stele engraved with the image of the deceased that is still preserved. In 1462, he donated a complete set of Buddhist canonical scriptures known as the Northern Yongle Tripitaka, printed from 1419-1440, together with large cabinets for their storage that are still preserved today in the Rulai Hall. This provided a major supplement to the original Buddhist texts that were housed in the Sutra Hall.

Like many Buddhist monasteries, Zhihua Temple served as a residence for monks, providing space for study and meditation, and welcoming worshippers to attend ceremonial observances and funeral services. As an important repository of Buddhist texts, Zhihua Temple in particular, whose name refers to the attainment of wisdom, may have served as a learning and teaching center.

The temple continued to have imperial support through the end of the Ming dynasty and into the early Qing (1644-1911). Later historians denounced Wang Zhen for his corruption and mismanagement that caused political disorder and the decline and fall of the Ming dynasty. In the eighteenth century a memorial to emperor Qianlong (r. 1736-1795) sought to dishonor Wang Zhen and resulted in the removal and destruction of his statue and shrine and the loss of imperial support. The temple fell into decline, and by the early twentieth century it was in a seriously dilapidated state. Monks began to rent out portions of its space to local businesses and residents and to sell its collections.

In late 1920s, the two magnificent coffered dragon ceilings were taken down and sold. The ceiling from the Zhihua Hall was acquired for the Philadelphia Museum of Art by Horace Jayne, curator the Oriental Art Department. Though accessioned into the collection in 1930, it was not until decades later in the 1950s, with the construction of the museum’s new wing, that the ceiling could be installed in a gallery that simulates a Chinese Buddhist temple space. Shown with it are Buddhist history acquired from different sources and large sections of a mural painting originally from a temple in Xinxiang prefecture, Henan.

The ceiling from the Ten Thousand Buddha Hall, at first sold to a coffin-maker, was acquired by Laurence Sickman in 1930 for the newly founded Nelson Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City. Together with the purchase of a huge mural painting of Assembly of Tejaprabha Buddha, taken from the Guangsheng temple in Hongdong, Shanxi province, and the lattice gate panels, the design of their large Chinese temple gallery took shape and is still a major feature of the museum.

Shortly afterward, the temple came to the notice of scholars. Prof. Liu Dunzhen, director of the Nanjing Central University Architecture Department made a study of the Zhihua temple and published a report on the Rulai Hall.

Though the temple survived the downfall of the Qing dynasty in 1911, the Republican era, and the communist revolution that established the People’s Republic in 1949 and abolished religious practice, the current complex is greatly reduced in size and is only about half of its original area (approximately 278 in length from north to south and 44.5 meters wide). In 1957, the Beijing office of Cultural Affairs declared the Zhihua Temple an architectural preservation site, and in the following year the Beijing city government cleared debris and made initial repairs. In 1984 the city established the Beijing Zhihua Temple Administration Office. State funding enabled extensive refurbishment in 1986, and in 1992 the temple was made the headquarters for the Beijing Cultural Heritage Exchanges Office. Today the temple is open to the public as a museum where visitors can see the restored temple halls and historic history and attend performances of Buddhist traditional music.

References:

Kinoshita, Hiromi. “Reimagining the Chinese Galleries at the Philadelphia Museum of Art,” Orientations, v. 50, no. 1.

Lu, Ling-en. “Buddhist Temple Reimagined: The Formation of the Chinese Temple Room in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in the 1930s,” (forthcoming in Exhibiting East Asian Art in a Global Context, a conference volume)

Beijing wenbo jiaoliu guan and Beijing shi Zhihuasi guanli chu. Gusha Zhihua si. (Beijing: Yanshan Press, 2005.

Mei Ninghua 梅宁化 and Shu Xiaofeng舒小峰. Gusha Zhihuasi 古刹智化寺. Beijing: Beijng Yanshan chubanshe, 2012.

Mingshi [History of the Ming Dynasty], Wang Zhen biography juan 304.

Tsai, Shi-shan Henry. The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty (Albany, State University of New York Press, 1996