Sculptures of Zhihua Temple

As recorded on the stelae dated 1444, the year of the Zhihua Temple’s construction, the temple buildings had lavish furnishings and sculptures of Buddhist divinities with polychrome ornament. Recent studies estimate that the temple had some thirty sculptural figures, mostly carved from wood, but many of them are no longer preserved. A recent review of the sculptures identified eleven important works that were in damaged condition and seriously in need of repairs. Beginning in 2004 a team of experts began to conduct extensive cleaning and repair of these figural images to restore their former appearance, reinforce, and stabilize them. Most of these are large principal sculptures that appear to be from the time of the construction of the Zhihua Temple. This section discusses a few of the main figural images and their significance within the contexts of their locations and groupings in the temple space.

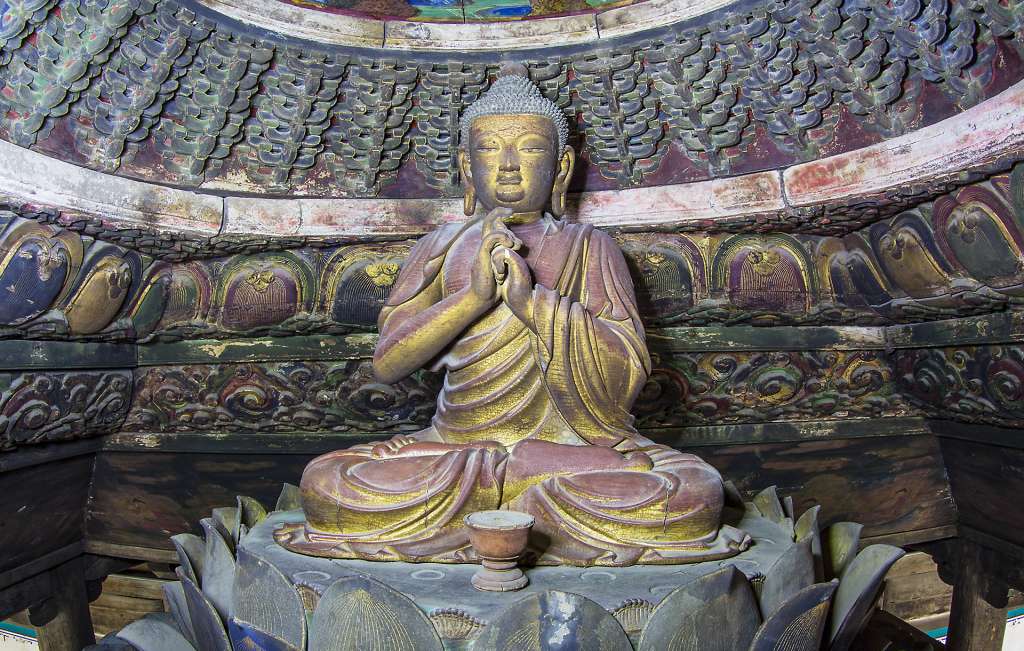

In the first large temple courtyard inside the Zhihua Gate, sculptures can be seen today in the Zhihua Hall on the north side of the courtyard that faces the gate and the Scripture Hall on the west side. The main altar of the Zhihua Hall is no longer in its original form, and the three large seated Buddhas that originally occupied the space were removed and are now believed to be in the Dajue Temple. The Zhihua Hall now houses three Buddha images that once occupied the Dabei Hall at the back of the temple. These sculptures are smaller in size than the former ones, but are likely quite similar in appearance. The three Buddhas are depicted sitting with legs crossed in front on lotus thrones. The elaborate throne bases are believed to be of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911).

They each wear a robe draped over the left shoulder that falls diagonally across the front of the torso and under the right arm leaving the chest, right shoulder, and arm exposed. They have curling hair and a jewel-like protuberance on the ushnisha on the top of the head. They are distinguished by the position of their hands. The central Buddha has his right hand reaching forward with fingers pointed downward in the gesture of touching the earth (bhumishparsha mudra). The Buddha to his left has the right hand raised in the gesture of granting absence of fear (abhaya mudra) The Buddha at his right side has both hands has both hands held in front of the chest in gesture of teaching, known as turning the wheel of the law (dharmachakra mudra). The three are identified as The Buddhas of the Three Ages—Shakyamuni (the central historical Buddha), Dipankara (Buddha of the Past), and Maitreya (Buddha of the Future). From the time of Shakyamuni’s life and his teachings to his disciples, the belief in the Buddha as the Enlightened One grew into a religion that spread across Asia and expanded doctrinally to include a universe of many Buddhas of countless ages in time and realms of the universe. The Zhihua Temple sculptures illustrate various aspects of these religious concepts.

The Rulai Hall (Tathagatha Hall) is named for a title given to the historical Buddha Shakyamuni, from whose enlightenment and teachings the Buddhist religion originated. Shakyamuni Buddha is the large central figure, finely carved, covered in gold, and more than four meters high. He displays the same pose as the central Buddha in the Zhihua Hall, with right hand touching the earth in front of him. On the walls around there are countless Buddhist figures set into small niches.

Shakyamuni is accompanied by two tall, crowned figures, standing at his sides, who wear long richly ornamented robes, unlike the plain robe of the Buddha. The robes have painted patterns of birds, peonies, dragons, and lions that simulate embroidery and finely woven textiles.

The figure at the Buddha’s right or west side is Indra 帝释天, the king of Hindu gods, who holds a large scepter. The one at the Buddha’s left, is the Hindu god Brahma 大梵天. The appearance of the Buddha together with Hindu gods Brahma and Indra is very unusual in Chinese Buddhist art, but can be identified with textual accounts of the Buddha’s life.

The earth-touching pose, bhumisparsha mudra, is associated with a key event in the prince Sakyamuni’s life, his achievement of enlightenment through profound meditation years after renouncing his privileged existence in order to seek the truth. Many depictions of the Buddha in the history of Asian art depict him seated in this pose to represent the moment, when on the verge of attaining enlightenment, the demon god Mara summoned a hoard of subordinate demons to distract him. By touching the earth, Shakyamuni called upon the earth goddess to witness his merit and overcome the demons. In the Rulai Hall, however, Mara’s demons are absent. The presence of the gods Brahma and Indra refer not to the moment prior to the enlightenment, but to events following the Buddha’s enlightenment when Brahma and Indra, along with many other gods, came to the Buddha to implore him to show others the way to achieve wisdom in a world full of ignorance. The Buddha therefore began to teach and gathered a following of disciples.

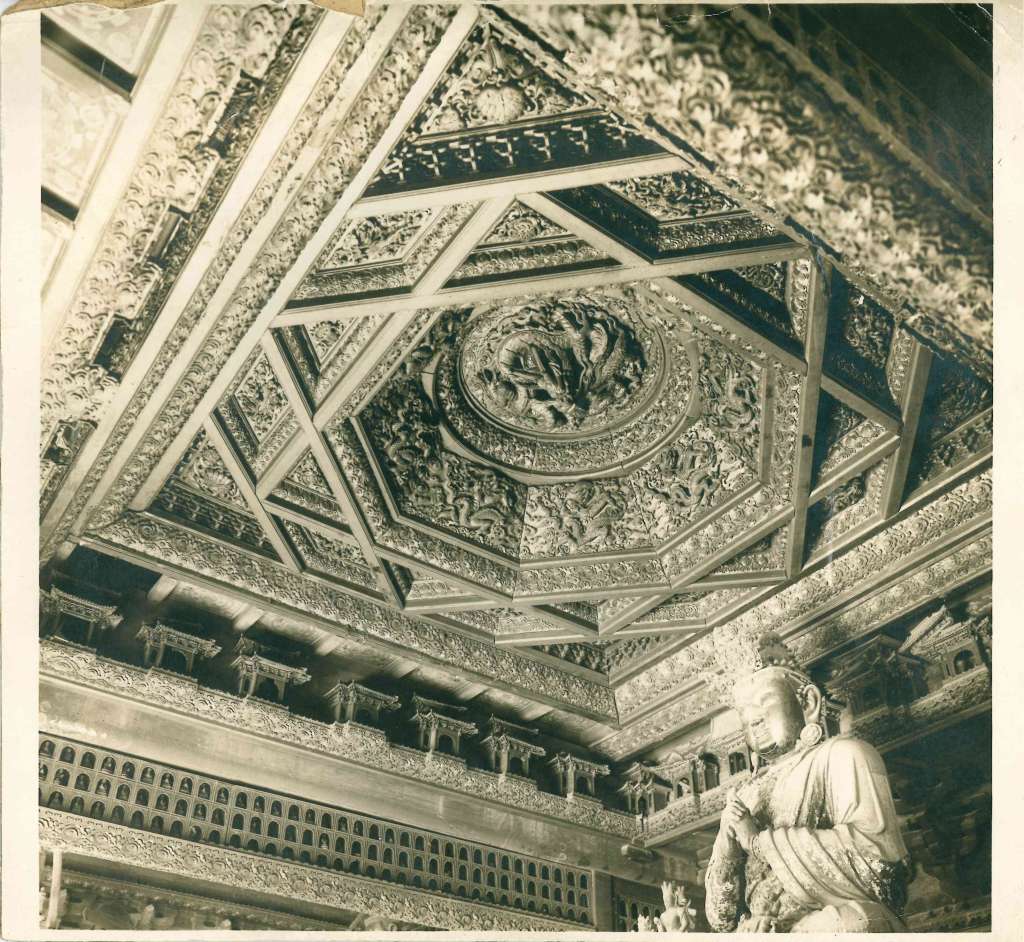

The three figures on the ground level of the Rulai Hall are located directly below three other large Buddha sculptural images in the upper level, called the Wanfoge (Ten-thousand Buddha Pavilion). Of these sculptures, the central figure is artistically similar to the Shakyamuni in the lower level. It too is a very large golden figure displaying finely modeled features and wearing the same kind of robe and earrings. In addition, this Buddha wears a five-petaled jeweled crown, large necklace and additional jewelry on his arms and ankles. He sits on a larger multilevel, thousand-petaled lotus throne set on an elaborately carved base that indicate his superior status or importance. His hands are held up in front of his chest, with the index finger of the left hand raised and the right hand closed over it. This is the mudra called the “wisdom fist” (also known as “single word golden wheel”) and is the gesture of the Buddha Vairocana who is the dharmakaya Buddha. A large coffered ceiling with central dragon was formerly situated directly above him.

After the death or parinirvana of Shakyamuni, different ways of perceiving the historical Buddha emerged, at first a distinction between his physical body and the body of his teachings. The human Buddha, remembered in the stories and at the sites of important events of his life, came to be regarded as a transformational and impermanent form, or nirmanakaya. His disciples began to compile the teachings, and this scriptural canon became associated with the term dharmakaya. Through the development of Buddhism as a religion, dharmakaya took on a higher abstract significance as embodiment of the transcendent and timeless essence of Buddhahood and the basis of all other manifestations of a Buddha’s qualities. The universal nature of Buddhahood is represented in the Wanfo Pavillion by the Vairochana Buddha and the 10,000 small Buddha on the surrounding walls.

The two other large Buddha sculptures in the Wanfoge are labeled as Sakyamuni Buddha and Rochana Buddha, and together with the central Vairochana they are identified as the Three Bodies of the Buddha. Rochana represents the Buddha body as sambhogakaya or baoshen, body of reward, an idealized vision worshipped by believers emerged.

The current Rochana and Shakyamuni sculptures at the side of the Vairochana Buddha show little resemblance to it and to the Buddha downstairs in the Rulaidian and appear to have been made at a different time and by different craftsmen. Although it is possible that the original plan for the Wanfo Pavilion may have included the representation of three Buddha bodies, these other two and show awkward proportions and less accomplished workmanship.

A Buddha in the Scripture Hall is closely related to the central Vairochana in the Wanfo Pavilion and holds his hands in the “wisdom fist” position. This much smaller but also finely carved figure is seated nearly out of sight at the top of the tall octagonal sutra cabinet that contains many drawers for storing volumes of Buddhist scriptures.

Small relief Buddhas appear on the front of the drawers. Each side of the octagonal cabinet also features elaborate carvings of divine animals and figures on the supporting columns and arches at the top. Above the Buddha there is a small, but elaborately constructed coffered ceiling with a central painted mandala, a tantric Buddhist ritual diagram. The artistic configuration of the Vairocana Buddha, and the scriptures housed in the precious cabinet and brings into close juxtaposition the concepts of Buddha dharma as the teachings, as objects of veneration, and as the essential dharmakaya.

The Zhihua Temple sculptures and tantric Buddhist features seen in the ceiling tiles and other elements are closely descended from Buddhist art of the earlier fifteenth century as known from the Yongle and Xuande reign periods. During Yongle reign period emperor Chengzu (r. 1403-1424) promoted extensive cultural and religious interaction with Tibet, inviting Tibetan monks to the capital and welcoming esoteric ritual practices. Chengzu tried to restore the relationship between imperial patrons and Tibetan lama preceptors that was established in the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) for their mutual benefit. Many fine works in gilt bronze, silk and lacquer were produced during the Yongle period that are similar to or derived from contemporary Tibetan art. Portable gilt bronze sculptures with engraved Yongle and Xuande reign designations were given to Tibetan monks and official envoys, some very similar in appearance to the much larger wooden sculptures in the Zhihuasi.

References:

Palace Museum Beijing 故宫博物院编. Ming Yongle Xuandi wenwu tezhan 明永乐宣德文物特展,紫禁城出版社2010年版.

蒋人和 Katherine Renhe Tsiang, “从艺术史的视角探讨智化寺的佛像 [Sculpture in the Zhihuasi: Some Art Historical Perspectives]”, Forthcoming in Beijing Zhihuasi. Wenwu Publishing House, 2022.

Lalitavistara 佛說普曜經, chapter 23 (西晉月氏三藏竺法護譯), Taisho shinshu diazo kyo. v. 3, no. 186, 528.

Mei Ninghua 梅宁化、Shu Xiaofeng舒小峰. Gucha Zhihuasi 古刹智化寺. 北京燕山出版, 2012.

Mingshi 明史 [Zhang Tingyu et al 張廷玉等, 1739], juan 304 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1997), v. 26: 7772.

Shen Weirong 沈衛榮, “Tantric Buddhism in Ming China,” in Orzech, Charles, Henrik Sorensen, and Richard Payne, eds. Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia (Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 4 China, vol. 24). Brill, 2010.

Ulrich von Schroeder, Indo-Tibetan Bronzes (Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications Ltd., 1981.

Xing Jizhu 邢继柱,Minghe qingshang: Ruibaoge cang jintong foxiang 《鸣鹤请赏:瑞宝阁藏金铜佛像 》Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House, 2012, no. 89 .

Yan Xue 閆雪. “Beijing Zhihua chansi zhuanlunzang chutan: Mingdai Hanzang fojiao jiaoliu yili 北京智化禪寺轉輪藏初探: 明代漢藏佛教交流一例 (A preliminary research on the revolving sutra case in the Zhihua Chan Monastery in Beijing: a case of the interaction between the Han and Tibetan Buddhism in the Ming dynasty).” Zhongguo zangxue 85 (2009, 1): 211-15.

Yang Zhiguo 杨志国:《智化寺明代佛像修复与保护》(Repair and conservation of Ming period sculptures in the Zhihuasi),中国文物保护技术协会编:《中国文物保护技术协会第六次学术年会论文集》,中国文物保护技术协会2009年版,187-195页